CASE STUDY

Röchling Automotive Shifts Gears to Make an Engine 35% Lighter

Engineering and manufacturing company Röchling Automotive was given an ambitious target by one of their automobile OEM customers: to reduce the weight of an engine by 35%. After partnering with Materialise to optimize, design, and cast an aluminum inlet and print in plastic around the metal core, they are on their way to meeting this goal. They started with a core engine component that has already been optimized over decades, and both sides have worked together to reach this ambitious target.

The challenge

Reduce engine weight by 35%

Greek philosopher Heraclitus is known for saying, “Change is the only constant in life.” Röchling could not agree more. In the late 1800s, they started to explore steel’s full potential for different markets, customers, products, and technologies to see how it would be more optimal than coal — the main technology at the time. In 2006, when plastics gave a lightweight-but-durable alternative, they saw that it solved some of their biggest problems in automotive, medical, and other industries.

Since then, the Röchling Group is a market leader in researching, testing, and applying plastics for new and challenging applications to add value and fix some of their customers’ pain points. It’s because of this mentality that they became an early adopter of 3D printing, starting to work with the technology over 15 years ago. Today, they continue to look to additive manufacturing for automotive because it has been proven to solve some of their biggest challenges.

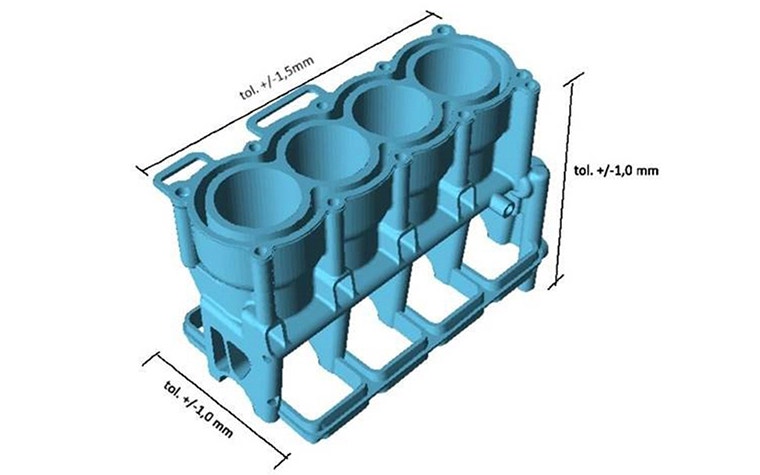

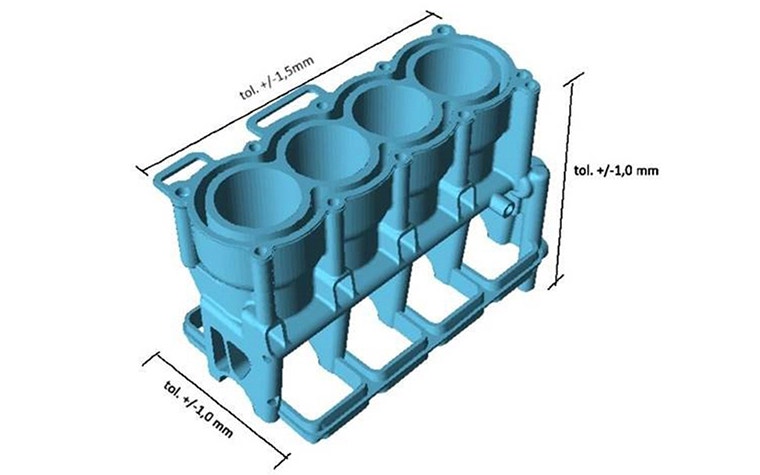

When a customer came to them and asked to reduce the weight of an engine by up to 35%, Röchling first considered how to trim metal off the design. If something is too heavy, then an easy win would be to remove any non-essential material. So, they pared down the amount of metal needed for the engine block as much as possible. But this wasn’t enough. They then looked into replacing the heavier metal areas with a more lightweight material.

The solution

Optimize design and use multiple materials

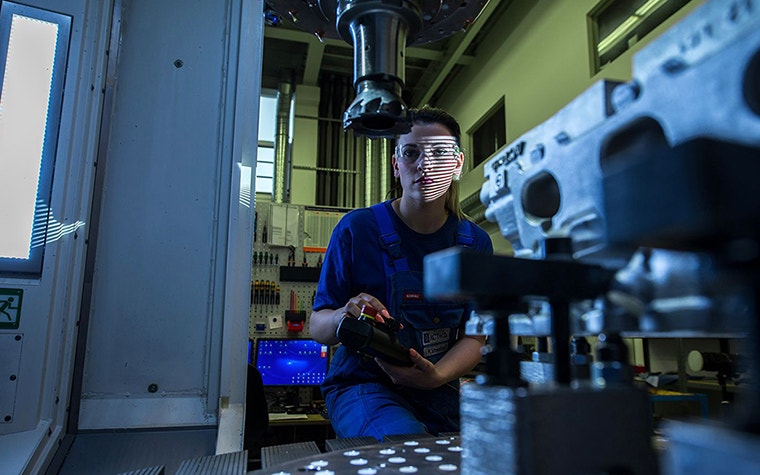

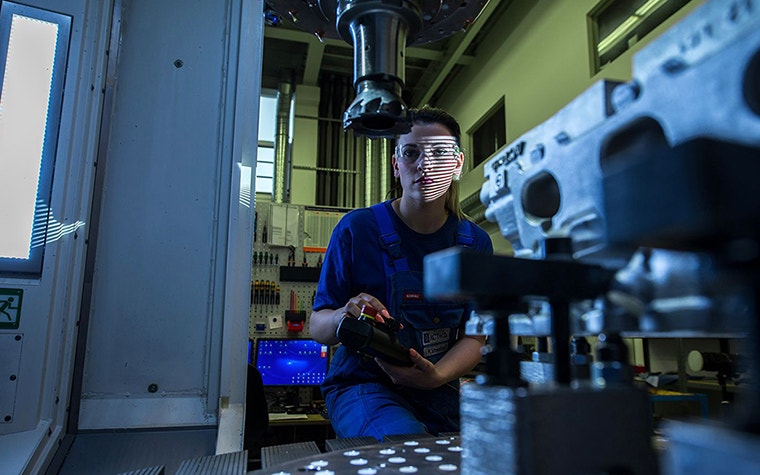

The combination of the two did the trick. ACTech, a Materialise company that specializes in rapid prototyping casts, produced the aluminum core of the cylinder block. They left in metal where the engine combustion happens — the part that has to hold up despite strong forces and high temperatures bearing down on it. The unusual geometry was easily converted into a ready-to-use prototype by using additive technology of 3D-printed sand mold packs.

In most engines, there is usually a metal casing around the inlet. However, the team found that this could be replaced with a strong plastic. Replacing the casing in plastic drastically cut down on the weight while having the right properties to hold the metal parts in place. However, the actual printing was quite complicated since it was a shell and therefore needed to be made in interlocking parts that could be constructed over the aluminum center. What the project team did was create all the parting planes and cut profiles in 20 portions altogether, with complex cuts to hide the cut marks as much as possible.

Once this was complete, the printing process began. More specifically, two models were printed in TuskXC2700T material using stereolithography, one of which was painted and the other which was left transparent. This one integrated part was printed so that it could be tested to further tweak and optimize.

Even though Röchling’s aim was to make a more lightweight engine, they are working in an industry where development times are getting faster and faster. As specialists in the field, ACTech has a wealth of experience creating designs with unusual shapes in the shortest amount of time possible. When coupled with 3D printing, the process goes much faster as changes can be made digitally with a few clicks instead of resetting large milling machines as was done in the past.

Materialise’s custom-made software is what ultimately lets these changes happen much faster — so there can quickly be a functional prototype that the designers can hold in their hands, examine, test, and define what they need in their next iteration. “The software is important. This is one thing we saw in Materialise that other 3D printing manufacturers don’t have,” said Fabrizio Barillari, Head of Product Line for Engines and Propulsion Solutions at Röchling Automotive.

The result

A lighter part and a true partner

Röchling knew that automotive 3D printing could make products more lightweight — ideal for the automobile industry that they are working in. But what they found by working with Materialise was more than just the end-product. They found a true partner that understands the industry and could advise them on how to design and print.

“With Materialise, we see the potential to truly work together — finding new materials, new processes — which bring additive manufacturing to the next level,” shared Fabrizio.

This process called co-creation, allows the two sides to have a closer working relationship. And the results have paid off: “In this industry, partnerships are vital. And when two partners really understand each other, then something really great can come out of it,” said Fabrizio.

“The prototype was exactly what we expected because we had constant communication with Materialise throughout the process. We really appreciate this. By working with Materialise, we could rely on their expertise and know-how and knew they were not biased to work only with one type of machine or technology. They understand the full spectrum, and this allows for the best product to be made. We could really create something great together.”

Share on:

This case study in a few words

Automotive

Stereolithography

Casting

TuskXC2700T

Aluminum

Weight reduction

Design optimization